Success flows in 20 years of innovations by HPD

APR 24, 2013

Robert Clarke, Honda Performance Development’s first employee, was invited to address associates and drivers from Honda-powered IZOD IndyCar Series teams for about 15 minutes this week in association with the company’s 20th anniversary.

“I started thinking about all the issues we had and said I think I need more like an hour,” said Clarke, retired president of HPD. “This was a brand new company and a brand new Honda company and a Honda company doing work that had never been done outside of Japan. I don’t think we really understood or appreciated what we signed up for until it was too late.”

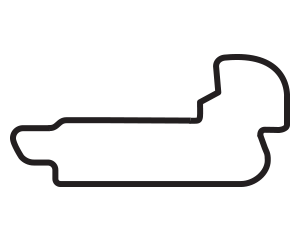

Today, HPD is the technical operations center for Honda's high-performance racing programs. It specializes in the design and development of race engines, chassis and performance parts and technical/race support based in a 123,000-square-foot facility in Santa Clarita, Calif.

Clarke smiles as he relates the specter of the project that has mushroomed over two decades with 197 Indy car victories. Still, he didn’t want to miss out on being on the ground floor.

“I worked in Honda Access and it was in the same building as R&D in Torrance (Calif.), and as a manager I had clearance that would allow me to go into confidential areas,” Clarke continued. “It was on one of those trips to speak with someone that I ran into this Indy car in the paint booth and it was being painted for the Detroit Auto Show announcement. I said, ‘What’s this?’ and they said, ‘Oh, we can’t talk about it.’ I found out about the announcement that Honda was going to go Indy car racing and I said I had to be part of it. Someone told me that Tom Elliott was the guy to talk to. The next day I had a resume on his desk.

“At that point I was the only employee (as general manager). I started with bullet points: Build a building. Hire the people. Create the organization. Win some races. Win the Indy 500. That was the immediate challenge.”

Clarke recounts a dinner early in his Honda career in which he was seated next to company founder Soichiro Honda, who at age 22 used a converted Curtis Wright aircraft engine to set a Japanese speed record of 75 mph.

“From him I understood how important racing was to Honda,” Clarke said. “Without racing, there is no Honda. It’s very much a part of Honda’s R&D that it’s OK to fail if you learn from it.”

Early on in the Indy car program, there were failures, disappointments and downright embarrassments, according to Clarke. Rahal Hogan Racing, an original test team in ’93, gave up on the Honda engine after the 1994 CART season.

“It was slow learning process with a lot of failure along the way,” Clarke recalled. “There is no road map; you just have to figure it out along the way. The test program that we ran in ’93 went quite well with an engine mostly developed by Mugen (owned by Mr. Honda’s son) and Honda R&D was focused on the F1 program. When R&D took on full responsibility, they couldn’t just take Mugen’s design, they had to do their own thing.

“They drew on all their Formula One experience, and that’s exotic gasoline and high-revving Formula One engines. When they got to methanol-burning V-8s, it was a different configuration and different combustion characteristics that they did not have the direct experience with and they started to fail.

“When we started racing in ’94 it was pretty much a disaster and came on the heels of Bobby failing to qualify for Indy in ’93 (with a Chevrolet engine). We were totally disgraced and even packed up and left before (the race). When Rahal abandoned Honda for a Penske (Ilmor D) engine, it caused us to totally restructure the engineering team and throw the engine away and start over with fresh engine that was introduced at Indy in ’95.”

Fortunes turned immediately for the revamped spec. Scott Goodyear started on the front row of the Indianapolis 500 and two months later Parker Johnstone earned the pole at Michigan International Speedway. Rookie Andre Ribeiro won the pole and race at Loudon on Aug. 20 -- 2½ years into program.

“With an all-new approach to the design, we got it right. More than right,” Clarke said. “In ’94, our best result was third by Rahal in Toronto.”

Victories were added through the end of the decade and the future was promising. But HPD came close to being shut down following the 2001 CART season chiefly because of a flap with Toyota that disintegrated into a court case over a pop-off valve spacer.

“We were losing confidence in CART after the pop-off valve spacer scenario,” Clarke said, noting that evidence came to light about the sanctioning body’s collusion with Toyota. “Trust is something that takes a long time to earn but is easily lost.

“On the Tuesday after the Houston race in 2001, the decision was made that we were going to quit. We agreed we would continue through 2002 and at Laguna Seca it was announced. The season ended at Fontana in October and for the next the four months I had repeated meetings trying to convince them we couldn’t shut it down.

“We won 123 races and six championships. All the goals that were established we either met or exceeded. There are other racing programs I said. Racing is our culture and why throw that away and start over again?”

Management agreed and before any associate could spend a dime of their severance package HPD was back in business and heading to INDYCAR for 2003. But its role had changed significantly from an engine build company to one that would design the engine, conduct R&D and produce it as the Japanese R&D component was focused on the Formula One program.

“It was like going back to the beginning,” Clarke said, “but it totally revitalized the company.”

It paired with Ilmor – another first for HPD and Honda to work with another engine company – in an effort to have a seamless transition. Its first year of competition was similar to its initial year in CART. Honda won two races.

Again, though, Honda started to get it right – to the point that it drove Toyota and Chevrolet away. For the 2006 season, it was asked to be the sole supplier to the IZOD IndyCar Series – a role it held in association with Ilmor until 2012 when engine manufacturer competition returned.

“It was something that Honda had never done before was races without competition,” added Clarke, who taught architecture at Texas Tech before joining Honda. “With that, there were more challenges than we imagined. We worried mainly about reliability.”

HPD went solo with the new specification of a consumer-relevant 2.2-liter, turbocharged V-6 engine fueled by ethanol for the 2012 IZOD IndyCar Series season. It most recently won the Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach and is poised for future success.

As Tetsuo Iwamura, President of American Honda Motor Co. and COO of North American Regional Operations, said: “One after the other, each of us must be ever vigilant, to relentlessly overcome each challenge, to reach higher, set more innovative goals, and bring joy to our customers. The company cannot rely on its past successes, but must willingly revitalize itself by challenging each associate to achieve a greater level of innovation.”

Twenty years later, Clarke can relate.