African American Pioneer ‘Rajo Jack’ Continues To Inspire

FEB 08, 2022

Note: INDYCAR.com is celebrating Black History Month with a series of content throughout February.

When the formation of Force Indy was announced in December 2020 as part of Penske Entertainment’s Race for Equality & Change, Team Principal Rod Reid said the team would run No. 99 on its cars as a tribute to an African American racing pioneer who yearned to compete in the Indianapolis 500 with that number but never got a chance.

That man was Dewey “Rajo Jack” Gatson.

Gatson’s story may not be as well-known as fellow trailblazing African American drivers such as Wendell Scott in NASCAR or Willy T. Ribbs in the INDYCAR SERIES, but it continues to inspire dreams of drivers and teams of color more than six decades after Gatson passed away.

“It's so important for us to know where we've come from,” Reid said. “There's a lot of history. African Americans have been in motorsports ever since the beginning of the car, the sport itself. I thought it would be fitting for us to take on that heritage and use the No. 99 to move forward.”

Gatson was born in 1905 in Tyler, Texas, the oldest of six children and son of a railroad worker. At age 16, he was hired as a laborer for the Doc Marcell Medicine Show, sort of a traveling circus of the day. Gatson immediately showed his natural mechanical skill, including modifying a truck into a mobile home for the traveling Marcell family. That led to him being put in charge of the show’s fleet of 20 vehicles from the group’s home bases in St. Johns, Oregon, and eventually Pasadena, California.

Skill with wrenches and vehicles also pivoted Gatson toward the racetrack in the 1920s, but with one much larger challenge than his non-Black counterparts. Racing, like most sports of the day, was segregated, and many organizations prohibited Black drivers from competition.

So, Gatson used a web of nicknames and deception to enter a variety of races up and down the West Coast in many different vehicles – stock cars, sedans, sprint cars, midgets, motorcycles and more. For example, when he entered his first race at a Northern California fair, Gatson used the name Jack DeSoto and said he was a native of Portugal. At other races, he said he was Native American or Morroccan to elude the prejudice of the day.

Another alias he used to fool promoters and sanctioning bodies was “Rajo Jack.” That came from his eventual job as a successful salesman in the Los Angeles region for Rajo Motor Manufacturing, which sold cylinder heads and speed kits for Ford Model T’s.

While the variety of aliases added to his mystery, Gatson’s talent behind the wheel was clear from the start.

He became a star up and down the West Coast, winning more than 30 so-called “outlaw races,” often in cars numbered 33 or 99. One of those major wins came in a stock Ford two-seater in 1936 at Los Angeles Speedway, an event he captured by more than two laps.

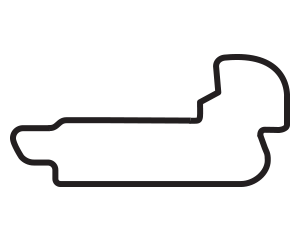

Other victories during the 1930s came at Silvergate Speedway in San Diego and Ascot Speedway near Los Angeles, and at tracks in Sacramento and Oakland, California.

When “Rajo Jack” won, another elaborate ruse based on his race took place in Victory Lane. Common practice at the time was for a trophy queen to present the winner with his award and give him a kiss. So, to avoid any controversy, Gatson’s wife, Ruth, presented him with his trophy and a kiss after most of his victories.

Ruth Gatson played a pivotal role in supporting her husband’s early success.

In April 1939, Dewey Gatson had his Miller engine in pieces to repair a main bearing the day before a race in Oakland, California. He called his wife to get ready for the drive. But instead of taking the wheel of the tow vehicle, Gatson stayed in the trailer and rebuilt the engine on the road while Ruth drove 400 miles to the Bay Area. “Rato Jack” qualified third and finished second in the race after the frantic repair job.

That hard-working attitude, on-track success and his genial nature led him to break through the color barrier and gain respect from his fellow drivers. But discrimination still existed among promoters and sanctioning bodies, and he never got a chance to compete at the highest level of the sport, including the Indianapolis 500.

Like many drivers, some of the prime years of Gatson’s career vanished when auto racing all but stopped in America during World War II. When the war ended, Gatson was losing sight in one of his eyes due to an accident while performing a motorcycle stunt in 1938.

Gatson retired after flipping in an accident while struggling to run mid-pack in 1947 at San Diego Speedway. But he couldn’t resist the lure of competition and returned to the cockpit, primarily with the American Racing Association in Northern California but also in selected races in the Midwest.

His last race came in 1954, at an AAA-sanctioned sprint car event in Honolulu. He was blind in the damaged eye, and his body was battered by other racing injuries.

But Gatson still was competitive and more importantly – he drove under his real name in his last race behind the wheel.

Gatson continued to sell auto parts and was working as a mechanic when he died of heart failure in February 1956 at age 50. Recognition of his superb driving career and as a pioneer for drivers of color took awhile but finally arrived. He was inducted into the West Coast Stock Car Hall of Fame in 2003 and the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame in 2007.

And his story of perseverance amid prejudice continues to inspire to this day.

“I have been in and around the sport for 40 years,” Reid said. “Force Indy remains a labor of love, and our goals are unchanged: focusing on diversity with an eye toward competing in the NTT INDYCAR SERIES and, in honor of Rajo Jack, the Indianapolis 500.”