Johnson Defies Usual Learning Curve as Progress Accelerates

JUL 16, 2021

The first NTT INDYCAR SERIES season of Jimmie Johnson has not been a reflection of what motorsports history knows of the seven-time NASCAR Cup Series champion. Or has it?

Johnson didn’t become an overnight success in NASCAR. Rather, he has told of spinning tires in the Xfinity Series, suffering stock car growing pains, crashing a few cars, studying the top drivers of the day, learning, improving, developing. Like many future stars before him, it took 58 races over four seasons with three different teams for Johnson to win an Xfinity race. When he moved to the Cup Series late in the 2001 season, his average finish for the year was 31.3.

It can be argued that the same process is underway in INDYCAR, where Johnson, at age 45, didn’t have the benefit of starting in a lower division as he had in NASCAR. In INDYCAR, Johnson is learning a new style of racing in a new car at new venues on a new team with different tools and facing the extraordinary challenge under the scrutiny of a national television audience fascinated by his acclimation to open-wheel racing.

“And first of all,” said Mike Hull, Chip Ganassi Racing’s managing director overseeing Johnson’s INDYCAR indoctrination, “remember that he doesn’t have to do this.”

For his part, Johnson has been transparent about the immense mountain he is climbing in INDYCAR, admitting his mistakes when they’ve occurred – and they have -- and being visibly humbled by the generational depth of this INDYCAR field. As Johnson told NBCSports.com earlier this month, “I’m now where I thought I’d be at Race 1.”

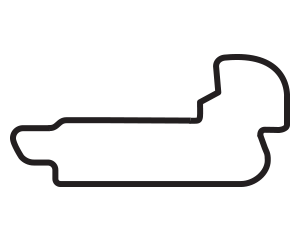

Indeed, there has been progress, and it is measurable. Whereas Johnson finished three laps behind the race winner in the season opener at Barber Motorsports Park and five laps off the pace the next week on the St. Petersburg, Florida street circuit, he has been only a single lap behind in four of the five most recent races – and in the other he had a throttle issue that sidelined him in the middle of the race.

Two of those races were held on Detroit’s Belle Isle Raceway, a temporary circuit that is universally considered INDYCAR’s most difficult. There, he shaved three seconds off his deficit from the first practice to qualifying. In Race 2, Johnson made what he described as his first legitimate pass of the season and was properly using push-to-pass on the laps prior to and following pit stops. However, a spin with 16 laps to go relegated him to the 21st finishing position.

“The potential these cars have is just so much higher (than in stock car racing),” Johnson told NBCSports.com. “To challenge yourself on the brakes, to challenge yourself through the center of the turn, let alone these high-speed turns that I look at and think, ‘There is no (expletive) way I can run wide open through that turn.’ And when you do it, (the car) drives better.

“If you lift, the thing’s a total handful, but if you commit to running it flat, the sucker sticks and you’re good. So, I’m making these huge gains.”

It is fascinating to watch, but it requires paying attention.

The overall results might not reflect it, but Johnson was racy at Road America in his sixth race and racier yet at the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course in his seventh. What lies ahead in the five remaining opportunities this season? Progress, Hull said, but Johnson and the team will not measure it against public perception.

“Progress in anyone’s ethic is measured by what (a person) thinks they got out of today,” Hull said. “Did they get the most out of the day?

“In your life or my life, if we don’t live our lives that way, so be it. But Jimmie lives his life measuring what he just did to help him for tomorrow, and that’s what is so special about him. He works really, really hard to get the most available out of every moment he has on this Earth, and he’s doing that with his racing program.

“That’s refreshing.”

Johnson chose to have Chip Ganassi Racing lead his bucket list chance at driving INDYCAR SERIES cars because the Indianapolis-based organization is rich in resources, experience and success. But consider this: Only Dario Franchitti – and maybe a young Dan Wheldon – joined Chip Ganassi’s team as a proven INDYCAR commodity. Jimmy Vasser didn’t. Alex Zanardi didn’t. Juan Pablo Montoya didn’t. Not even Scott Dixon did. Many in the sport even questioned the hiring of Alex Palou, and now the 24-year-old Spaniard who led only a single lap late in his lone INDYCAR season holds a commanding 39-point lead heading to the season’s final six races, beginning with the Big Machine Music City Grand Prix on Aug. 8 in Nashville, Tennessee.

Johnson is merely the latest driver in what could be called Ganassi’s “development” program, and his progress is being measured internally. Hull said it starts with the effort Johnson has made to the program.

“He comes to work every day, and he is not mailing it in,” Hull said. “He’s engaged with the people who have their hands on his car, he’s engaged with the people who have their minds on his car, with the people who commercially sponsor his car, with his teammates, with the (team) owner, with the entire process of what it takes to be a race driver, and he doesn’t have time for anything else.

“He’s already won seven NASCAR championships and 83 (Cup) races -- he’s already done what most race car drivers are envious of doing, and many of them think they would have done that ‘if’ certain things had happened. Jimmie Johnson has taken ‘if’ and erased it from his lifestyle.”

Johnson’s INDYCAR program is still in its infancy, and Hull said members of the Ganassi organization still have to resist the temptation to be starstruck by Johnson, who, as Hull said, “walks into a racing room and lights it up.”

“I mean, he’s a legitimate legend, and I don’t want to use that word because it often is reserved for people who are retired,” Hull said. “But he’s accomplished such great things in motor racing that you have to step back in the daily process and not be in awe of that.

“As a group of people, you have to go about your business to give the athlete everything he or she needs for them to look in the mirror at the end of the day and say, ‘I got the most out of it.’”

Johnson can do that because he is doing the little things, such as greeting Hull and other staffers with to-do texts before they’ve even gotten out of bed. In engineering meetings, Johnson is all ears and questions, measuring his progress corner by corner, lap by lap, day by day. Where will it end? With progress if not results.

At Road America, Johnson was on pace for a season-best finish, perhaps as high as 12th, before sliding off course on cold tires. Without that, he likely finishes on the lead lap in a race where 14 of the 25 drivers have won races in this series. That’s progress, and it is driven by Johnson’s improved confidence not only in what the car is capable of but by what he has learned he is capable of in this new cockpit.

“Certainly,” Hull said. “That’s where Jimmie is at today, getting better with each day.”