OLSON: INDYCAR's youth movement is good except when it's not

OCT 02, 2018

The scene backstage before driver introductions last month at Sonoma Raceway wasn’t typical. The driver getting the most attention was a 19-year-old rookie. Veteran drivers, usually not given to fawn over newbies, were fawning over Patricio O’Ward.

One by one, they shook his hand and welcomed him to the club after he qualified fifth for the Verizon IndyCar Series season finale. O’Ward, the 2018 Indy Lights champion, smiled throughout, savoring his welcome-to-the-big-league moment.

A few weeks before that scene, O’Ward had spoken in a telephone interview about the possibilities of moving from Indy Lights to the Verizon IndyCar Series in the future. “I’m pretty confident you’ll see me in an Indy car in the next few years,” he said.

OK, so it was a conservative estimate.

OK, so it was a conservative estimate.

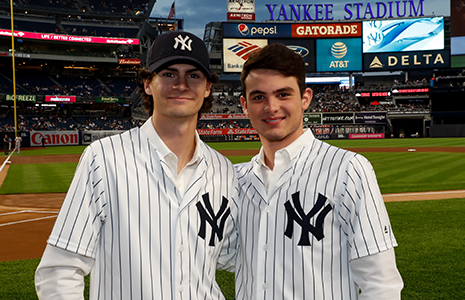

The positives of the Sept. 19 announcement that O’Ward and Colton Herta will join the re-badged Harding Steinbrenner Racing team for 2019 are obvious: Two talented young drivers advance from the Mazda Road to Indy program to the show.

Underlying the obvious is the parallel advancement of team co-owner George Michael Steinbrenner IV, a move that brings attention, money, a famous sports name and a 22-year-old owner to the series. And did we mention Al Unser Jr. will be coaching them? Yeah, that too.

“Having two young drivers -- rookies -- come into the series is not something you really see happen,” Steinbrenner said during the announcement. “Obviously having Al Unser Jr. there to coach them is very reassuring for two kids under 20 to learn how to present themselves on and off the track. Having Al onboard and having his experience with the two young guys, it will certainly make for a great, great teaching moment from Al.”

It’s a shining moment for the team, the series and two young drivers with enormous potential. It’s also an ode to the Mazda Road to Indy program. This sentence should be copied and saved for future pasting: Since its inception in 2011, MRTI has produced X IndyCar drivers and Y champions.

(The current answers would be X = 12 and Y = one. Check back often for revisions.)

In August at Portland, Herta had his first laps in an Indy car while O’Ward watched closely. “If I ever get into an Indy car,” Herta said a few days later, “I’ll already know what to expect from the car. “We’ll be able to go from there. It was a special day. I loved every second of it.”

But there’s a “but” to all of this, right? Of course there is. For every driver who reaches the top level, legitimate candidates remain on the outside looking in. For every O’Ward and Herta, there’s a Gabby Chaves and Conor Daly. There’s an Ed Jones, a Sage Karam, a Zachary Claman de Melo, a Stefan Wilson, a Jack Harvey and a JR Hildebrand. There are dozens of drivers with solid professional resumes watching from the pits.

In a perfect world, all would have full-time rides. All deserve full-time rides. But racing isn’t a perfect world.

So we take the good news with the bad, always hoping the bad news gets better. In a year in which the car count went up and the fields became deeper and stronger, capable drivers still were left out. That’s not the fault of anyone, just a statement of fact. More quality drivers exist than cars. That’s a good problem to have, unless you’re one of those left out.

So, if you have an off-season wish list, here’s one to put at the top:

More cars, please. Pronto.