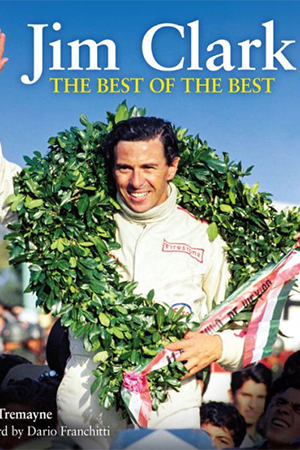

Franchitti foreword helps make Clark book 'Best of the Best'

NOV 09, 2018

“I’ve always had the impression that with (Jim Clark) it was a case not of ‘Why am I so quick?’ but ‘Why is everybody so slow?’ But it was so easy for him. He had the sort of talent that made everything he did seem effortless. Jackie (Stewart) did so much in his own career, raced against some of the very best and beat them, yet he still holds Jim in awe. That says it all for me.”

-- Dario Franchitti’s foreword in “Jim Clark: The Best of the Best” by David Tremayne

Dario Franchitti has two racing heroes. He never met Jim Clark, but he knows Sir Jackie Stewart quite well. Stewart was instrumental in Franchitti’s career, hiring him to drive in junior formulas in the early 1990s. Clark died in a crash at Hockenheim in 1968, five years before Franchitti was born, but the legend of a fellow Scotsman followed and inspired Franchitti through a career that included three Indianapolis 500 wins and four Verizon IndyCar Series championships.

Aside from books, films and photographs, Franchitti knows Clark by way of witness. He has sought those who knew Clark, especially those who raced against him. Stewart was among them, along with a few other legends.

“One of the great things about winning a few races is that I got to spend time with a lot of those guys who raced (Clark), people who were my heroes,” Franchitti writes in the foreword. “And whether it was Dan Gurney, Mario Andretti or A.J. Foyt, they respected him. A.J. isn’t impressed by anyone, but he talks about Jim Clark in very warm, very positive terms. He was impressed by his talent, but also by his character.”

“One of the great things about winning a few races is that I got to spend time with a lot of those guys who raced (Clark), people who were my heroes,” Franchitti writes in the foreword. “And whether it was Dan Gurney, Mario Andretti or A.J. Foyt, they respected him. A.J. isn’t impressed by anyone, but he talks about Jim Clark in very warm, very positive terms. He was impressed by his talent, but also by his character.”

Franchitti’s fascination about and devotion to Clark’s life story explain why David Tremayne chose him to write the foreword for “Jim Clark: The Best of the Best,” which tells of the talent and complicated humility of Clark, who won 25 grands prix, two Formula One championships and the 1965 Indianapolis 500.

When Tremayne, the celebrated author of 50 books and F1 correspondent for The Independent, contacted Franchitti about writing the book’s foreword, he marveled at the swift response.

“It’s the only time in history that I’ve ever texted him and gotten an immediate reply,” Tremayne said with a chuckle. “I think he and (brother) Marino are the two drivers I’ve met who know the most about racing history. Most drivers think history began when they started racing, but these guys have a deference about racing history. They know so much about it.”

The 520-page, 21-chapter hardcover book details Clark’s talent, his determination, his racing accomplishments – he still stands ninth on F1’s list of all-time victories – and his occasional bouts of indecision. Franchitti knows such stories well.

“Jackie always tells the story that they were out in the middle of nowhere, just the two of them, with Jim at the wheel, driving somewhere,” Franchitti recalled. “They got to a crossroads and had only two choices – left or right. They had one decision to make, and Jim couldn’t make it. They just sat there. His indecisiveness was well known outside the race car, but his personality changed when he was in it.”

Clark was raised on a 1,200-acre farm near Duns in the Scottish Borders, about 20 miles east-southeast of Edinburgh. He had an interest in sports as a boy – mainly rugby, cricket, hockey and tennis – but he also enjoyed the farm’s machinery, including various trucks and tractors. Had it not been for his remarkable proficiency for driving fast cars, he likely would’ve continued his other vocational passion – farming.

Hill climbs and road rallies in the late 1950s led to sports cars, which eventually led to a GT race in a Lotus Elite coupe at Brands Hatch in 1958. Clark finished second behind Colin Chapman that day. Chapman later hired Clark to drive a junior formula car, and the two were a formidable duo for much of what was about to come.

In the beginning, though, Clark’s parents, James and Helen, weren’t supportive of their son’s hobby-turned-profession.

“As events pushed him ever closer to the international stage, however, his increasing

attraction to racing brought him into greater conflict with his parents,” Tremayne writes. “Theirs was not merely the concern that might be understandable in a mother and father for an only son, as they must have been all too aware of the danger of motor racing in that era, but there was a practical aspect of it too because of his role on the farms.

“(Childhood friend) George Campbell never heard any of the family arguments, but he knew they were happening.

“‘We never got into it. And they were too disciplined for that. But his father was really hard on Jim. And his mother tried hard to stop him with the motor racing that year.’

“But James Clark was proud of his son’s ability in a race car.”

By the time Clark decided to follow Chapman to Indianapolis in 1963, he was coming off a runner-up finish in the F1 world championship the previous season, including a victory in the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. At Indy, the rear-engine Lotus was both fast and unreliable. Still, he finished second to Parnelli Jones in his first try. The next year, he won the pole and led 14 laps before a tire blew, damaging the suspension and ending Clark’s race. He returned in ‘65 as the favorite, starting on the front row and beating Jones and Andretti to the finish line.

By the time Clark decided to follow Chapman to Indianapolis in 1963, he was coming off a runner-up finish in the F1 world championship the previous season, including a victory in the U.S. Grand Prix at Watkins Glen. At Indy, the rear-engine Lotus was both fast and unreliable. Still, he finished second to Parnelli Jones in his first try. The next year, he won the pole and led 14 laps before a tire blew, damaging the suspension and ending Clark’s race. He returned in ‘65 as the favorite, starting on the front row and beating Jones and Andretti to the finish line.

“Jimmy drove that car with understeer,” Tremayne explained. “Most drivers hate understeer and can’t make it work, but he had this technique to make understeer work for him. That was part of his ability to drive around any problem and to adapt to what the car did. So many people say, ‘Well, he had the best car,’ but I’m not so sure that was true.”

Racers come in all forms. Some are savants, others perfectionists. Some can be insufferable or arrogant or both. Clark was different, and his difference has become as much a part of his legend as his racing skills. If you didn’t know he was Jim Clark, championship racer, he wasn’t about to tell you. Highly intelligent, unnervingly polite and at times excruciatingly shy, Clark didn’t create a fuss about himself. But that didn’t mean he was a milquetoast.

“It was well-known that he bit his nails and was a quiet guy who didn’t like speaking in public,” Franchitti said. “But there were other parts of his personality. He certainly wasn’t a pushover. If he felt somebody had done something wrong, he’d go straight at them. He was quite a strong personality, but, as a lot of people from Scotland are, he was under the radar about it.”

Clark knew he had a gift, and he worked diligently to perfect it. He wasn’t just competing against the best drivers of his time, he was beating them. He also wasn’t talking about it, possibly because he wasn’t thoroughly sold on his own skills, especially in the early years. It was hard enough to convince Clark of his own talent, let alone anyone else.

“To begin with, there was an uncertainty or an unwillingness to admit publicly that he thought he was quite good,” Tremayne said. “That would never have been his nature, anyway. Eventually, he realized he was very good. There was this type of paradox, if you like. In the early stages, he wouldn’t admit it to himself, and then later on he knew inside himself how good he was, but he was never going to tell the world that that’s what he thought. He was so good that he didn’t need to go around telling everyone.

“The greatest appeal of Jim Clark was that he was such a genius and he was so good at what he did, but there was this fundamental humility that he never lost.”

On the 50th anniversary of Clark’s Indy win, Franchitti climbed into the cockpit of the Lotus 38/1 Clark drove that day and did a few delicate laps around Indianapolis Motor Speedway’s historic track. The look on his face – before, during and after – was a mix of awe, joy and understanding. The familiar green car, with its simple, cigar-shaped body and profound, bundle-of-snakes yellow exhaust pipes, only further intrigued Franchitti. He already had devoted an entire room of his home to Clark memorabilia, but he wanted to know more about the man.

When he read Tremayne’s manuscript, he found it.

“David hadn’t gone through the normal sources a lot of the time; he’d gone beyond that and found other stories,” Franchitti said. “He did a lot of detective work on that. I read some stuff that I didn’t know, and I read some stuff that I knew but I didn’t think I’d ever see in print. It was really cool. It’s a great book. When he asked me to do it (write the foreword), I was absolutely honored. I said to him at the time, ‘I didn’t know Jim.’ David said, ‘Don’t worry about it. I think you’re the guy to do it.’”

That says it all, indeed.

“Jim Clark: The Best of the Best” is available at numerous online outlets, including evropublishing.com, amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com.