Recognizing Takuma: How Indy 500 winner's life has changed, Part 2

MAY 22, 2018

(“Recognizing Takuma” is a three-part series for IndyCar.com that records the changes the 41-year-old Japanese driver has experienced since winning the 101st Indianapolis 500 presented by PennGrade Motor Oil a year ago. This is the second installment.)

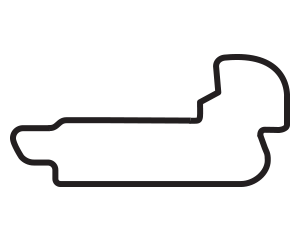

When Indy cars raced at Twin Ring Motegi, a 1.54-mile oval about 90 miles north of downtown Tokyo, American racers marveled at the autograph sessions. Usually predictable affairs in the U.S. – fans stand in line to wait for drivers to sign and pose for photos – autograph sessions at Motegi were far from predictable. They were part spectacle, part ritual and entirely wonderful.

In Japan, it’s a tradition called zōtō – gift giving – and it’s customary in a variety of social situations, one of which is the greeting of sports heroes. Receiving an autograph from an honored racer requires a gift from the autograph seeker, and not just any old gift. Typically, racers signing autographs in Japan received elaborate, handmade gifts – paintings, sculptures, framed photographs, even food – relating to the person whose autograph is sought.

In the two times Takuma Sato raced with the Verizon IndyCar Series at Motegi, the length of his autograph line doubled the others. In his homeland, Sato has been on a level with the country’s greatest sports heroes – recently retired baseball legend Ichiro Suzuki, golfers Hideki Matsuyama and Ryo Ishikawa, and 2006 Olympic gold medalist figure skater Shizuka Arakawa, to name a few – since he broke into Formula One in 2002.

In the two times Takuma Sato raced with the Verizon IndyCar Series at Motegi, the length of his autograph line doubled the others. In his homeland, Sato has been on a level with the country’s greatest sports heroes – recently retired baseball legend Ichiro Suzuki, golfers Hideki Matsuyama and Ryo Ishikawa, and 2006 Olympic gold medalist figure skater Shizuka Arakawa, to name a few – since he broke into Formula One in 2002.

That fame and sense of national pride has only expanded since Sato won the 101st Indianapolis 500 last year. Japan has a long and storied motorsports history; 20 Japanese drivers have competed in Formula One, nine in INDYCAR. But winning the Indianapolis 500 turned Sato into his country’s A.J. Foyt, and his home fans – without a nearby INDYCAR venue to see him race and bring him gifts – now travel abroad to see him race and bring him gifts.

During an interview last month at Barber Motorsports Park, Sato sat in the office of one of the Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing transporters. When the subject of gifts from Japanese fans was raised, Sato gestured at a neatly arranged stack of boxes behind him. All gifts, just from a weekend in Alabama.

“Generally speaking, Japanese fans get very majestic and royal about racing,” he said. “I’ve seen so many fans fly over from Japan to the States just to see a race just for the weekend. They have to request a day off from work before they leave and the Monday after the race to travel back. That’s a great deal of commitment. It’s not cheap, either, but they come.

“Some of the fans will come four or five times during the year. That’s unbelievable. Every time they come, they bring some kind of gift or snacks. That doesn’t just happen because I won the Indy 500. This has been happening for seven or eight years, but the number has increased this year. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate it.”

In November, he returned the gift, traveling to Japan with the Borg-Warner Trophy, which had never left the U.S. in its 82-year existence. For two weeks, the 5-foot, 4-inch, 153-pound sterling silver trophy featuring likenesses of every Indy 500 winner made as many appearances in Japan as possible, often with the person whose likeness was added most recently.

“Over the course of a week or 10 days, it went all over Japan,” Sato said. “It was very successful. Fans were able to physically see it up close. It’s such a beautiful trophy. For a lot of those awards and events, I appeared with the trophy. I felt such appreciation for that. Had I not won the race, the trophy never would’ve visited Japan. Because of the win, people really reacted. It was fantastic. A lot of people got really emotional when they saw it.”

The reaction of fans seeing the trophy for the first time was almost as special for Sato as the reaction of fans to seeing him drive the car he used to win the Indy 500. After the race, Andretti Autosport carefully cleaned and restored the blue-and-white No. 26 to its pre-race glory. Honda broke down and refreshed the engine, and off it went to Motegi to join the trophy.

“The main event was when I drove the car,” Sato said, smiling at the recollection. “That sound was exactly the same as the Indy 500. It was the same engine and same spec. People got really emotional. During the earthquake in 2011, the oval speedway at Motegi was damaged. Although they used it briefly for the demonstration, INDYCAR hasn’t been back to Motegi since 2011. It was the first time an Indy car had driven at Twin Ring Motegi since then. It was very emotional for Japanese fans. Thirty thousand people attended that event. It was fantastic.”

Back in the States, Sato continued his tour, meeting dignitaries, celebrities and sports stars. Before the Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach last month, he threw out the ceremonial first pitch at a Los Angeles Angels game, where he met countryman Shohei Ohtani, the rookie pitcher who also hits monstrous home runs. Sato didn’t know he’d be throwing the pitch until days before the game, so he studied and practiced.

Back in the States, Sato continued his tour, meeting dignitaries, celebrities and sports stars. Before the Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach last month, he threw out the ceremonial first pitch at a Los Angeles Angels game, where he met countryman Shohei Ohtani, the rookie pitcher who also hits monstrous home runs. Sato didn’t know he’d be throwing the pitch until days before the game, so he studied and practiced.

“About four days before we left Indy, they told me I’d be doing the first pitch,” Sato explained. “I was like, ‘Oh.’ I knew I was in trouble. I don’t know the form, I don’t know what the general rule is, and I don’t know how to throw the ball. So I watched YouTube every day. It was snowing in Indy, so I had to practice in my bedroom. … During the warmup, I practiced with a photographer. It was a huge crowd. I was nervous, but I think I did OK.”

The circle of people close to Sato in the U.S. is much smaller than the crowd that night in Anaheim – a handful of team owners, engineers, mechanics, journalists, publicists and managers. He’s been with four teams in his nine years in INDYCAR, including a second stint with his current team. When Andretti Autosport considered moving from Honda to Chevrolet during the offseason, Sato sought an opening with a Honda team and landed back at Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing.

A journeyman's resume like Sato’s might indicate difficulties, but detractors – if they even exist – are difficult to find. Sato has a reputation for being fierce and brave behind the wheel but kind and grateful away from it. He is supremely confident but not overbearing. Mostly, though, he’s known for what some drivers struggle to provide: feedback.

“He’s an absolutely impressive professional,” RLL engineer Eddie Jones said. “He’s very knowledgeable technically. That, of course, is a great help to engineering. He really understands the cars, the technology and the implications of handling and performance. From that standpoint, it’s really pleasurable to work with him. He’s a great asset to the team. I couldn’t be happier that he’s joined the team and that I’m actually working with him. Everything is very positive on that front.”

“He’s an absolutely impressive professional,” RLL engineer Eddie Jones said. “He’s very knowledgeable technically. That, of course, is a great help to engineering. He really understands the cars, the technology and the implications of handling and performance. From that standpoint, it’s really pleasurable to work with him. He’s a great asset to the team. I couldn’t be happier that he’s joined the team and that I’m actually working with him. Everything is very positive on that front.”

The start to the 2018 season hasn’t been up to Sato’s standards. He’s 13th in the drivers’ standings heading into Sunday’s 102nd Indianapolis 500 presented by PennGrade Motor Oil. He’s had only two top-10 finishes in the first five races – eighth at Barber Motorsports Park and 10th in the INDYCAR Grand Prix. Frustrating as it is, 2018 is nothing like Sato’s previous season with Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing, when he crashed out of four of the 15 races. So far this year, he hasn’t had any contact.

“The guy has always been very focused and very determined,” said Ricardo Nault, RLL’s team manager who worked with Sato during his first run with the team in 2012. “That hasn’t changed. He knows a little bit better what he wants out of the car – how he expects it to handle and what he expects to see from the team and the communication from our side. He’s still the hard-driving guy we had back on ‘12; he’s just a little bit more mature. He considers the implications of his actions a little bit more. We had a lot of wrecks back in the day, but he’s been very good about taking care of the car and very good with his feedback.”

If Sato’s feedback is precise, then the feedback of his fans back home is spot-on. In the year since his unexpected victory at Indy, viewership of Verizon IndyCar Series races has increased noticeably. If anything has changed in the past year, Sato says, it’s that people are paying more attention to him.

“I know it has increased the numbers of viewers in Japan, especially through the internet,” Sato said. “And TV is up significantly. Gradually it’s increased over the years, but 2017 at Indy made another huge impact. People are very happy about it in Japan, and now, of course, I have so much more positive support, not only in Japan, but in the United States, too. People have been really nice to me, and I’ve got great support here.”

With great support, of course, comes great gifts.

NEXT IN THE SERIES: Scott Dixon has free lamb for life from New Zealand. Helio Castroneves is a rock star in Brazil. But Takuma Sato has never-ending adulation from his homeland. Winning the Indy 500 has that effect on people and their countries.