Recognizing Takuma: How Indy 500 winner's life has changed, Part 1

MAY 21, 2018

(“Recognizing Takuma” is a three-part series that records the changes the 41-year-old Japanese driver has experienced since winning the 101st Indianapolis 500 a year ago. This is the first installment.)

These days, Takuma Sato can’t go anywhere in Indianapolis without being recognized. Strangers approach him in restaurants, malls and airports – especially airports – and offer heartfelt congratulations.

“Without saying anything, at 6:30 in the morning, I’ll get recognized by TSA workers as I go through security at the Indy airport,” Sato says. “They’ll say, ‘Where’s your ring?’ It’s like, ‘Wow.’ I’ll just be wearing regular clothes, no logo, and people know who I am.”

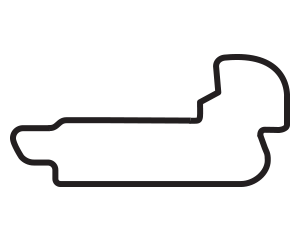

A cynic would point to the airport’s oversized photograph and display of Sato and his victory last year in the 101st Indianapolis 500 presented by PennGrade Motor Oil as the reason for the recognition, but the explanation isn’t that simple. Sato gets noticed everywhere in Indianapolis nowadays. A connoisseur of shrimp cocktail, he has a number of choices of local restaurants that serve his favorite dish. Wasn’t that long ago, he could enjoy it without being seen. Now, he enjoys it while being seen, and he likes it.

“People genuinely enjoy having a little chat,” he says. “Almost everywhere I go in Indy, I get recognized. That’s fantastic.”

“People genuinely enjoy having a little chat,” he says. “Almost everywhere I go in Indy, I get recognized. That’s fantastic.”

Takuma Sato’s life has changed conclusively since he prevailed in an electrifying duel with Helio Castroneves a year ago. He’s met world leaders, thrown ceremonial first pitches, appeared on talk shows, changed teams, driven his winning car before 30,000 fans in Japan, and traveled his homeland with the Borg-Warner Trophy – the first time the iconic Indianapolis 500 trophy has left the United States.

But mostly, he gets recognized in the city where it happened and at the races that led up to it.

“I’ve felt a huge increase in the reaction here in the States since I won the 500,” Sato says. “In autograph queueing, I’ve felt a greater reaction. People bring cards and photos and say nice things. It’s increased more significantly here in the States than it has in Japan.”

That’s true in part because Sato was a hero in Japan long before he won the Indy 500. In the U.S., he wasn’t nearly as famous before 2017, known only among serious race fans, the kind that closely follow Formula One. That’s where a 25-year-old racer from Tokyo first appeared on the global stage in 2002, driving for DHL Jordan Honda.

Sato’s F1 journey lasted through seven seasons and three Honda-related teams. His best race, coincidentally, was a third-place effort behind Michael Schumacher and Rubens Barrichello in the 2004 U.S. Grand Prix at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Eventually, Honda left F1 as a constructor following the 2008 season, so Sato was unemployed for a year.

Sato landed in INDYCAR for the 2010 season with KV Racing Technology at a time when Honda supplied the entire field. In the U.S., the results were better, but still not what Sato expected.

He started slowly with KVRT, crashing out of nine races in his first season. The following year, he won pole positions at Iowa and Edmonton. In 2012, he moved to Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing, posting podium finishes at Edmonton and Sao Paulo. In 2013, he moved to AJ Foyt Racing and scored his first Verizon IndyCar Series victory, at Long Beach.

He stayed with Foyt until heading to Andretti Autosport last year – a fortuitous decision considering Michael Andretti’s team had won two of the previous three Indianapolis 500s.

Before winning the 500 last May, Sato’s spin while trying to win it in 2012 with the Rahal team was his most renowned moment. While trying to go underneath Dario Franchitti for the lead in Turn 1 on the final lap, Sato couldn’t hold it. He spun and crashed, and Franchitti won. Minutes later, Sato left the infield medical center wearing a hat that read: “NO ATTACK, NO CHANCE.”

Before winning the 500 last May, Sato’s spin while trying to win it in 2012 with the Rahal team was his most renowned moment. While trying to go underneath Dario Franchitti for the lead in Turn 1 on the final lap, Sato couldn’t hold it. He spun and crashed, and Franchitti won. Minutes later, Sato left the infield medical center wearing a hat that read: “NO ATTACK, NO CHANCE.”

Five years later, the attack and the chance returned in all caps. Sato dodged and diced with Castroneves during the final laps last year, winning by 0.2011 of a second and changing his life forever. Now, TSA agents joke about his Indy 500 ring. Waiters want to talk to him while serving shrimp cocktail. Fans want to meet him. Kids want to be him.

“Generally speaking, I receive much more attention,” Sato explained. “It’s more awareness. The Japanese fans have known me for a long time, and they haven’t seen anything change, really. But a lot of people who didn’t know much about me now recognize me as an Indy 500 champion. I get a lot more great support from fans. That’s one significant thing that has happened.”

Sato’s primary charitable cause since 2011 has been helping victims of the earthquake and tsunami and aftereffects that devastated his home country, work he continues today. Sato is the first Japanese driver to win the Indy 500. In the days after the win, Terry Frei, a columnist for The Denver Post, was fired for a racially insensitive tweet about Sato, who responded by saying it was “unfortunate” and “sad” that Frei lost his job, then quickly transitioned to positive comments received from fans.

Perhaps, above all else, that’s what the TSA agents and waiters and fans notice. The grace and dignity of it all.

“He’s extremely popular,” said Eddie Jones, Sato’s lead engineer at Rahal Letterman Lanigan Racing, the team he’s returned to in 2018 to drive the No. 30 Mi-Jack/Panasonic Honda. “He’s a great draw for all of the Japanese fans, but it goes beyond that.

“At the INDYCAR Grand Prix last week, I was on the grid with him. It was American fan after American fan who wanted to take photographs with him and get autographs. Of course, he’s very obliging. He really is a popular character.”

NEXT IN THE SERIES: Sato takes the Borg-Warner Trophy out of the U.S. for the first time, throws a baseball for the first time, and drives the meticulously restored No. 26 Andretti Autosport Honda car that won the Indy 500 before a crowd of 30,000 fans in Japan.