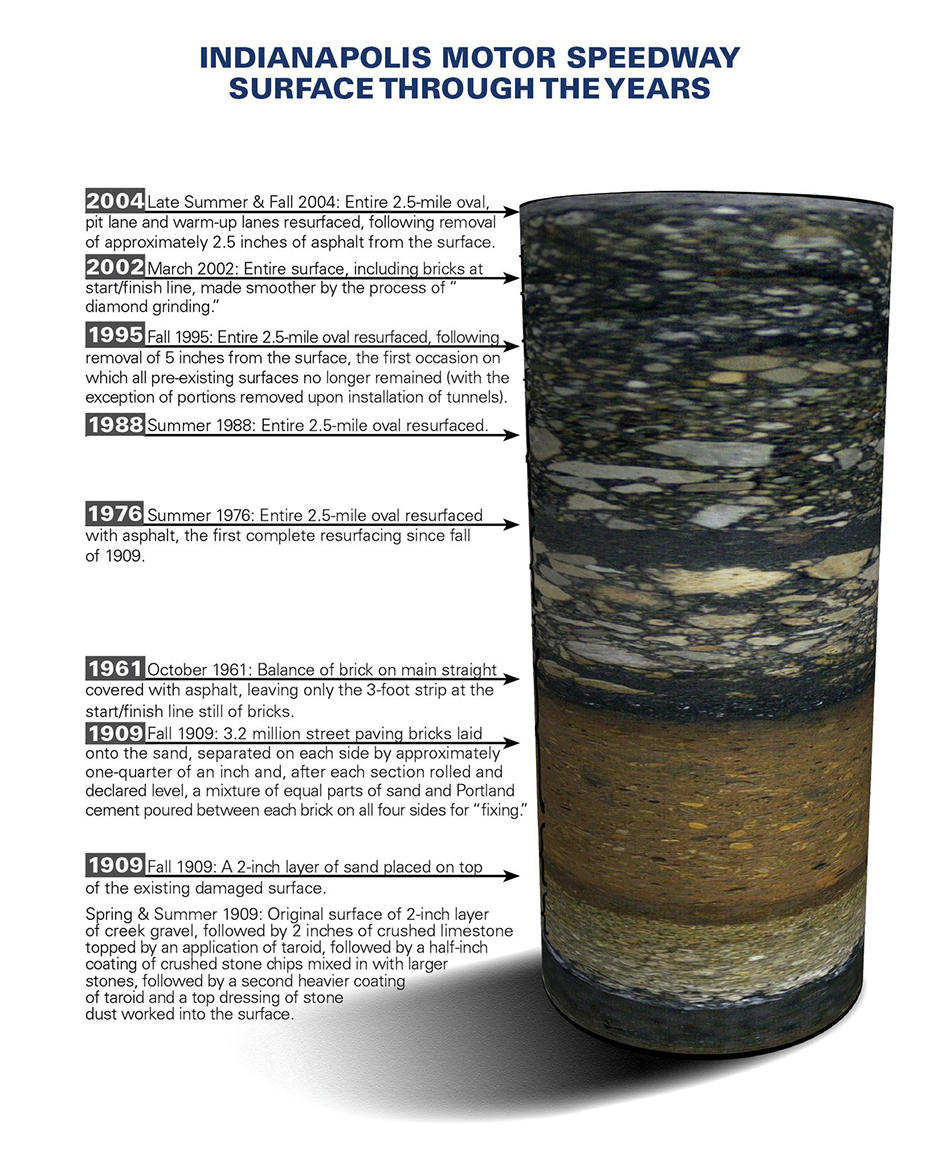

Core samples put Indy's majestic track history on visual display

NOV 11, 2017

Indianapolis Motor Speedway President Doug Boles stared into the layers of history and was overwhelmed with perspective.

The recent removal of three track cores from the famed 2.5-mile oval offered a visual trip back in time as Boles and track workers inspected the various surface levels, beginning at the bottom with the paving bricks originally laid in 1909.

“When that core came up and it was the bricks, that brick was (put in place) 108 years ago, they were installing those bricks and that brick has been in that spot for 108 years,” Boles said of the track’s initial paved surface.

He thought of how those paving bricks at the exit of Turn 3 were eventually covered in asphalt in the late 1930s.

“When they resurfaced the corners, that brick hasn’t seen the light of day in more than 70 years,” Boles said. “Not only did they race on it, that brick has been there from the very beginning.

“The racing it has seen and to be able to pull it out, it makes you feel pretty good about the fact that you’re always out talking about the history and how important it is and it’s not just history you read about in a textbook, yearbook or an article, it’s history that’s still in the racetrack. It’s very powerful.”

The moment of appreciation for the evolution of Indianapolis Motor Speedway’s track surfaces had to be remembered for posterity. Boles pulled out his cellphone, took photos and tweeted about it.

.@IMS history is mesmerizing. Track work 2Day included core samples & brick at bottom of this core was laid 108 years ago almost to the day! pic.twitter.com/euek21wawl

— J. Douglas Boles (@jdouglas4) October 27, 2017

He didn’t anticipate the reaction from not just avid race fans but history buffs. Many wanted to buy one of the cores. Media across the nation also picked up on it. Dozens of local TV newscasts showed Boles’ photo as the anchors spoke in amazement of the track’s iconic history come to life.

“When you saw all that together in that one six-inch-diameter, 18-inch core, it was almost emotional,” Boles said. “I took a picture and tweeted it, not thinking that anybody would care except for that real hard-core, geeky fan like me, who just really lives and breathes that history.

“To see the way that has taken off has been pretty crazy. It’s been beyond race fans. It’s people who love history.”

The cores aren't for sale. The plan is to put the best one on display at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum so this rich piece of history can be celebrated with the public.

Boles thought about the different levels of asphalt that have been laid atop the bricks over the years, too, specifically about the famous drivers who raced on those surfaces.

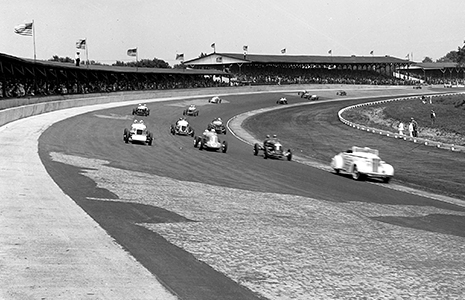

“From a surface standpoint, you look at the four major repaves we’ve had in our history,” he said. “The first time the whole track was paved at one time was in ’76, and you have someone like A.J. Foyt win on that surface (in 1977, with the pace lap shown at left) and Rick Mears win his first race on that surface (in 1979).

“From a surface standpoint, you look at the four major repaves we’ve had in our history,” he said. “The first time the whole track was paved at one time was in ’76, and you have someone like A.J. Foyt win on that surface (in 1977, with the pace lap shown at left) and Rick Mears win his first race on that surface (in 1979).

“Then you roll our way into ’88, it brings a new surface and that surface begins to see a lot more change in the speeds to the point that in ’95, when we resurfaced and the cars came back in ’96, the grip level is so high and the cars were in such a way that the track record still stands today from the ’96 resurface, which is pretty amazing.”

And to see the current surface holding up so well was a source of pride.

“The neat thing about the 2004 resurface, we’re in our 13th year of that resurface,” Boles said. “Going back to the technology of the asphalt, we’ve gotten 13 years and next year will be our 14th year of service out of that resurfacing, which is the longest we’ve gone without having to resurface the racetrack. It is good mileage.”

Longtime IMS historian Donald Davidson offers a wealth of knowledge on the track’s evolution, beginning with how that original track of paving bricks was a grinding test of endurance for drivers in the Indianapolis 500. It’s so much different today than when Ray Harroun steered a yellow No. 32 Marmon Wasp to victory in the inaugural Indianapolis 500 Mile Sweepstakes in 1911.

“It was very rough,” Davidson said. “What was required of a driver is quite a bit different than it is now. It was a lot of physical punishment. It’s still extremely demanding now, but it was so physical back then. The drivers, some of them were big and brawny, and the event was an enduro. Now it’s a series of sprints.

“Then, you sat out there all day and it was six hours, then it was five, then four and three-quarters. You wouldn’t stop that many times. You didn’t have pack-ups for yellows. On several occasions, the winner would go the distance on one (pit) stop. Several did that. You’re out there for hour after hour after hour, and normally the winner would go the distance but relief drivers were common.”

The original track surface wasn’t paving bricks. Davidson advises that in 1909 after preliminary grading, there was a two-inch layer of creek gravel, two inches of crushed limestone topped by an application of taroid (solution of tar and oil), then a half-inch coating of crushed stone chips worked in by heavy rollers to merge in between larger-size stones. After a second heavier coating of taroid, a top dressing of stone dust was worked into the surface by six-ton rollers. That surface proved unsafe in a series of races that year.

In the fall of 1909, a two-inch layer of sand was placed on the top of the existing damaged surface, then 3,200,000 street paving bricks were installed. They were separated by approximately a quarter of an inch. After each section was rolled and declared level, a mixture of sand and Portland cement was poured between each brick on all four sides for “fixing.”

In the fall of 1909, a two-inch layer of sand was placed on the top of the existing damaged surface, then 3,200,000 street paving bricks were installed. They were separated by approximately a quarter of an inch. After each section was rolled and declared level, a mixture of sand and Portland cement was poured between each brick on all four sides for “fixing.”

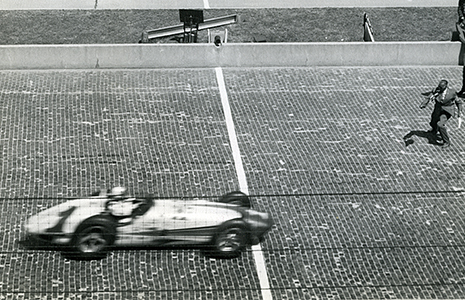

Asphalt was first added in 1936 (pace lap shown at left) to patch areas that were deteriorating in the corners. A year later, all four turns and part of the front straight entering Turn 1 were covered with asphalt. The short chutes between the turns were covered with asphalt in 1938 and the backstretch in 1939, leaving only most of the frontstretch with visible bricks.

“When just the main straightaway wasn’t paved in the late ‘40s, early ‘50s, some of the drivers were complaining about how rough the frontstretch was,” Davidson said. “Tommy Milton, who was the chief steward, said, ‘Back in my day when the track was bricks, the backstretch was so rough we were happy to get to the frontstretch.’”

Milton was a two-time Indianapolis 500 winner in 1921 and 1923.

“From ’35 to ’40, it was totally different because by the time you get to the summer of ’39, when they did (pave) the backstretch, when you come back in 1940 the whole track is asphalt except for about the 700 yards of the main straightaway,” Davidson said. “Anybody who had raced there before, by 1940 it’s a lot smoother than it had been.”

The first of Foyt’s four Indianapolis 500 wins came in 1961 (he's shown at left taking the checkered flag). It was also the last time “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing” occurred with a brick frontstretch. In October that year, those front-straight paving bricks were with asphalt, leaving just a three-foot strip at the start/finish line that exists today and is commonly known as “the yard of bricks.”

The first of Foyt’s four Indianapolis 500 wins came in 1961 (he's shown at left taking the checkered flag). It was also the last time “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing” occurred with a brick frontstretch. In October that year, those front-straight paving bricks were with asphalt, leaving just a three-foot strip at the start/finish line that exists today and is commonly known as “the yard of bricks.”

“Anyone running in ’61 and coming back in ’62, you saw the difference in surfaces,” Davidson said. “You had the clack-clack at the start/finish line where the bricks are (the sound the cars made as they quickly changed surface from asphalt to brick and back to asphalt).

“In ’61 and earlier, you come off of Turn 4 on asphalt and come down the straightaway a little bit and you’d hit the bricks and you’re shuddering and bouncing around all over the place and it’s fish-tailing and you’re steering like mad to gather it all up, then you hit the asphalt again after about 15 seconds and you’re going into Turn 1 and you’re on smooth asphalt again.”

Davidson estimates that 85 percent of the track today contains all the original surfaces and resurfaces underneath. The exceptions are areas where tunnels underneath the track have been installed and the surfaces had to be removed during construction. Asphalt only was used to “bridge” the track surface over the tunnels.

Boles had the core samples taken late last month to examine how the surfaces have handled the years of racing.

“They’re always settling, moving and expanding,” he said. “They expand and settle at a different rate than the asphalt, and each layer of asphalt expands and contracts at a different rate than the other layers.

“For the most part, the five lanes of asphalt that are in the corners, they look as if they were just resurfaced. They’re holding up really well. Hopefully we’ll get another two to five years out of this surface before we resurface again.”

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway oval will play host to the 102nd Running of the Indianapolis 500 presented by PennGrade Motor Oil on May 27, 2018. It is the sixth of 17 races on the Verizon IndyCar Series schedule. Tickets are available at IMS.com.