Driving demands force different training regimens for INDYCAR vs. F1

OCT 30, 2016

Whether you're driving in the Verizon IndyCar Series or Formula One, the mechanics of being lightning quick are pretty much the same: throttle, brake, turn, accelerate (repeat as necessary).

Although the tremendous athletic demands on the drivers are also comparable, a few differences make switching from F1 to an Indy car not as plug-and-play as many think. Alexander Rossi and Max Chilton, both 25, were Verizon IndyCar Series rookies in 2016, but their lengthy European open-wheel backgrounds that included time in the F1 paddock provide them the ideal perspective to discuss those distinctions.

“The thing about an Indy car that surprised me the first time I drove it — and I guess it shouldn't have — but a lot of people don't realize that an Indy car actually makes quite a lot more downforce than an F1 car,” said Rossi, the No. 98 Andretti-Herta Autosport Honda driver who won the 100th Running of the Indianapolis 500 presented by PennGrade Motor Oil and collected Sunoco Rookie of the Year honors for both that prized race and the season as a whole.

“The cornering capabilities, even though the car is heavier and has less horsepower, is comparable to an F1 car, if not probably higher.”

“The cornering capabilities, even though the car is heavier and has less horsepower, is comparable to an F1 car, if not probably higher.”

With Verizon IndyCar Series regulations not allowing power steering, the Indy car puts much more stress on a driver’s wrists, arms and shoulders than an F1 racer when the aerodynamic load piles on and dramatically increases the effort needed to turn the car.

In response to the particular demands of driving his Honda, Rossi adjusted the mix of his training regime this year. It also helped that, unlike in F1, Verizon IndyCar Series minimum car weight regulations do not include the driver in the calculation. Instead, INDYCAR follows an equivalency formula of 185 pounds – the combination of driver weight with added metal ballast – so each car carries the same weight and lighter drivers don’t have an advantage over their taller, heavier competitors.

“F1 very much focused on the weight and because of my height (6 feet, 1 inch) that was always the main focus for me,” said Rossi, the Californian who has been a reserve driver with F1's Manor Racing since 2014, made five starts with the team in 2015 and still serves as a reserve driver in 2016.

“I'd say 80 percent of my training was cardio and 20 percent was strength in F1, and now it's probably 60 to 70 percent strength and the rest cardio. With (no) power steering and the lateral forces we experience (in Indy cars), you need to have the upper body strength.”

Essentially, Rossi shifted the cardio levels he developed for F1 to a maintenance program to allow more pure strength training to respond to the increased physical demands of INDYCAR. Rossi adjusted his workout routine after his first oval race in Phoenix in April and feels he's had the right fitness balance since the change.

While some do not believe that racing drivers are athletes in a sport with tremendous physical demands, science proves them wrong.

Dr. Stephen Olvey, who served as director of medical affairs for the pioneering fulltime Indy car medical team in Championship Auto Racing Teams from 1978-2003, studied Indy car drivers a decade ago to measure the fitness requirements of racing against other sports. The study by Olvey, now an associate professor of Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery at the University of Miami and founding fellow of the Federation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) Institute for Motorsports Safety, found that the oxygen needs of an Indy car driver are comparable to an elite athlete in a 1,500-meter swimming event or a marathon.

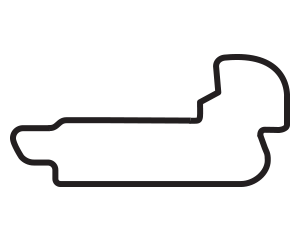

With the increased downforce of today's Indy cars compared to a decade ago, it's likely that baseline has risen even higher since the Dallara IR-12 chassis was introduced in 2012 and aerodynamic bodywork kits added in 2015.

With the increased downforce of today's Indy cars compared to a decade ago, it's likely that baseline has risen even higher since the Dallara IR-12 chassis was introduced in 2012 and aerodynamic bodywork kits added in 2015.

Chilton, the other Verizon IndyCar Series rookie with F1 experience who drove the No. 8 Gallagher Chip Ganassi Racing Chevrolet in 2016, also upped his physical game, especially when it came to his wrists and forearms. The Brit also found ovals put his upper-body strength to the test.

“Short oval racing is very physically demanding, so somewhere like Iowa Speedway, you just feel your wrists and hands getting tense within 20 laps — and you have to do 300 laps — so it takes some getting used to,” said Chilton, who raced with the F1 Marussia team for two seasons beginning in 2013.

“I also have this hand exercise where I tense and load up about 20 kilograms (45 pounds) of force and practice my forearm strength.”

While there are some corners on permanent road courses where F1 drivers experience several times the force of gravity shoving them around in the cockpit, it lasts for two or three seconds per lap and then it's gone. On the other hand, the short 0.894-mile Iowa Speedway punishes Verizon IndyCar Series drivers’ bodies with high sustained pressure up to six times the force of gravity for roughly half of the 18-second lap, something that pushes the limits of even the fittest athletes.

Lateral G-forces on an oval put huge pressure on the driver's right arm and shoulder because that side of the body is constantly pressed into the seat and side of the car.

“In F1, it's a short point where you get the peak G-force; in INDYCAR, it's a huge loading, loading, loading, loading that you just can't believe,” said Chilton, who holds the record for most consecutive finishes from the start of an F1 career at 25 races. “I think a lot of F1 drivers would be shocked by the amount of G-force.”

“In F1, it's a short point where you get the peak G-force; in INDYCAR, it's a huge loading, loading, loading, loading that you just can't believe,” said Chilton, who holds the record for most consecutive finishes from the start of an F1 career at 25 races. “I think a lot of F1 drivers would be shocked by the amount of G-force.”

Although he makes sure to focus on the strength needed to perform at the highest level, Rossi also quickly discovered that his cardiovascular training comes in pretty handy in an Indy car.

“The other thing that surprised me is that because you are under so much load in the corners, you can't really breathe,” Rossi said.

“The cardio has to be there as well because on the straights that you have, you need to recover the breath. In turns 1, 2, 3 and 4 of both Phoenix (International Raceway) and Iowa, you are not breathing — there's too much force, you can't do it. So you kind of hold your breath and then you need to have to have the aerobic capacity to bring your heart rate down in five or six seconds.”

Interestingly, one place where Chilton feels there's more force and less finesse in F1 is the braking, where stopping the lighter cars requires a much harder initial slam on the pedal than an Indy car. While he doesn’t doubt for a second that INDYCAR drivers have the strength to stomp an F1 pedal with sufficient force, the method of slowing the car isn’t exactly the same.

“It's a very small difference but a driver can tell,” Chilton said.

“In F1, the first hit of the brake application, you can hit it as hard as you like and it's unlikely the car will lock up unless it's wet. You get as much physical pressure straight away as you can and then feed off. You have to be slightly more finessed in INDYCAR because the car weighs more and it's easier to lock up.”